Kotaku-ji: Quiet Temple, Cool Details

You might think it would be pretty shady if a guy with five different names suddenly took off overseas and disappeared into the Chinese countryside. But that is exactly what Dogen Zenji (a.k.a. Dogen Kigen, Eihei Dogen, Koso Joyo Daishi and Bussho Dento Kokushi) did in 1223 as a monk of the Tendai sect of Buddhism.

Far from being shady, Dogen was in search of a more authentic form of Buddhism – and after some time traveling through China he found it, in a style of Chan Buddhism taught by a man named Rujing. Finally satisfied after a quest that had spanned five years, Dogen returned to Japan and began sharing his newfound views on the importance of zazen (sitting meditation).

Dogen’s ideas didn’t go over too well with the enlightened establishment in his hometown of Kyoto, and after a few years of derision took off to do his own thing in present-day Fukui where, in 1244, he built Eihei-ji Temple and established the Soto school of Zen Buddhism, which has since become the largest of the three traditional Zen sects in Japanese Buddhism.

Eihei-ji, meanwhile, remains as one of two head temples of Soto Zen Buddhism, spiritual center of some 15,000 Soto temples spread throughout Japan.

Kotaku-ji Temple in Matsumoto is one of them.

In 1399 Ogasawara Nagahide was appointed Lord of Shinano, continuing the line of Ogasawaras ruling this area from Igawa Castle. It took until early October of the following year for Nagahide to actually get his butt up here from Kyoto. From there it only took him a couple of weeks to be driven back out, in a series of battles with the local ‘ji-samurai’ warriors who evidently preferred to rule themselves. It wasn’t until 1432 that Nagahide’s younger brother Masayasu was handed the reins as the new Lord of Shinano and made up for his brother’s ill-fated reign by restoring the Ogasawara clan’s rule. He founded Kotaku-ji Temple in 1441 as the Ogasawara clan’s ‘bodai-ji’ (family temple). And this is where we are headed today.

‘Wonderful,’ you say. (I can hear you, you know.) ‘Just what I need. Another trip to another temple.’

Okay sure, temples can all start looking the same after a while. But there are always details that differ – and Kotaku-ji is no exception. Take a look at the picture of the temple gate above. That little Christmas tree-shaped thing in the middle of the gate’s crossbeam is the “sankaibishi”, the mon (emblem) of the Ogasawara clan. Designed from three overlaid rhombuses, this mon is said to be a derivative of the four-rhombus mon of the Takeda clan who rampaged through the area in 1550. Keep your eyes open as you explore the temple grounds, you will see more sankaibishi if you look closely enough.

The black stone pylon standing among the roots of a gnarled tree in front of the temple gate bear characters that read So-kuro-mon, referencing the black gate. The connection to the gate that stands now may seem obvious, but look around on the opposite side for a stone with a square hole cut into it. Conceivably, this stone could have been part of the base of a gate that no longer exists – perhaps the original black temple gate. (Speculation, maybe, but there are a few stones just like this on top of Higashi-yama where Hayashi Castle once stood.)

As we make our way up the path among the 400-year-old keyaki (Japanese Zelkova) we see, set back to the right a bit, a stone statue of a person with an expression of love and peace holding an infant. Two more small ones crawl at his feet. The large characters carved into the circular part of the pedestal read “Mizuko-jizo”. Jizo statues are a virtually ubiquitous element of Japanese Buddhist temples. Mizuko-jizo like this one represent the guardians of stillborn children, or children who died very young – guardians who help these children travel safely to the next world.

Jizo are also often found in temple gatherings of six, as well as along roadsides throughout Japan, offering protection to all of us mere mortals who seek such supernatural support.

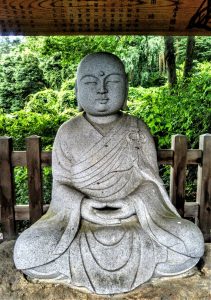

Zazen, as mentioned above, is an integral element of Soto Zen Buddhism. So it is no coincidence that the Buddha found along the path up to Kotaku-ji is sitting in the zazen tradition. He is also holding his hands in the Dhyana Mudra position, said to promote balance of body, mind and spirit. (I think I may finally bite the bullet and give this a shot myself.)

On my most recent trip to Kotaku-ji (i.e. this morning) I had the good fortune to run into the 31st in the generational line of Kotaku-ji temple priests, a man who simply introduced himself as ‘Ogasawara’ (yes, that Ogasawara). In a room off to the side of the main prayer hall he explained (over tea, fresh fruit and lightly-salted cucumber) that Kotaku-ji was originally a temple of the Rinzai sect of Buddhism, with Jigen-ji Temple of the Echizen Province (present-day Fukui) as its head temple. Along the way, however, Kotaku-ji made the switch to Soto Buddhism. Ogasawara-san says there are no records indicating when this happened, though one online source states Lord Ogasawara Mochinaga initiated the change in 1449.

Above your head as you pass through the gate at the top of our first long set of stone steps hangs the name of this temple – sort of. Right to left the characters read 龍雲山 – “Ryu-un-zan”, meaning Dragon Cloud Mountain. There is not, as far as the woman at the temple I spoke with last week knew, any mountain around here with such a name. Rather, it is taken from founder Ogasawara Masayasu’s legal name, which was, and I quote, “龍雲寺殿天関正透”.

*As a side note, owing to the Chinese tradition of attaching names of mountains to temples, even those Japanese Buddhist temples sitting on flat land have mountain names, called san-go, in addition to the actual temple names.

At the top of our second long set of stone steps we finally arrive at the main temple buildings, with the prayer hall right in front of us. To the left at our feet are two stone rabbits, related to “Usagida”, the Rabbit Field, and the related tale spelled out in this previous post.

There are more rabbits in the carved wood above the doors to the hondo, the main prayer hall, along with a couple of snakes that seem to be frightening the rabbits not one bit. Across the upper facade of the hall are the other ten animals of the Chinese zodiac. (You may also recognize the significance of the twin wooden adornments on the doors to the hall.)

To the left is the Kannon-do, the hall housing a statue of the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy, Kannon. Like jizo, statues of Kannon are quite common among Buddhist temples in Japan.

Of particular if trivial interest here is this Kannon’s inclusion among the Shinshu-Tsukama sanjusan-ka-sho Kannon Reijo (信州筑摩三十三カ所観音霊場), the 33 Kannon of Shinshu-Tsukama. These are specially designated places throughout the area where Kannon is enshrined. The Kannon-do here at Kotaku-ji happens to be Number One one the list. (Whether this carries any significance I can’t say for sure.)

Additional aspects of Kotaku-ji common to Buddhist temples in Japan are the large bronze bell hanging high above those little stone rabbits and the many family grave sites both below and to the sides of the temple grounds.

Among these graves, however, are a few pieces of history not to be missed.

Follow the path along the side of the Kannon-do, through the gate and into the trees. To your right there will be a sign and a set of stone steps. Start heading up, and make your first quick right.

This path leading higher up into the hillside forest will soon take you to this modest structure, built to honor two of the many legends of the Ogasawara clan.

After Ieyasu Tokugawa established his rule as shogun of all Japan in 1603 there was nevertheless some resistance. The greatest threat to the nascent Tokugawa shogunate was the Toyotomi clan, headed by Toyotomi Hideyori. The Tokugawa shogunate solidified its standing as the ruler of a unified Japan in the Seige of Osaka, which consisted of two campaigns, the first in the winter of 1614 and the second in the following summer. It was in this Summer of 1615 Seige that Ogasawara Hidemasa and his son Tadanaga both died in battle, fighting on the side of the Tokugawa clan. Here on the hillside behind Kotaku-ji is where the grave markers of Hidemasa and Tadanaga can be found.

Along a separate path branching off of the one leading here can be found one more important grave site. As mentioned above, I spoke this morning with the thirty-first generation priest of Kotaku-ji. The first, Sessho Ichijun Zenshi (雪窓一純禪師), rests here for all eternity along with the twenty-eight successive Kotaku-ji temple priests who have kept the faith here for close to six hundred years.

This morning, as I made my slow way up the stone steps, I heard a deer calling out from somewhere nearby. “We see deer around here quite often,” Ogasawara’s wife would tell me later.

As if there weren’t enough here to keep me coming back.

As Kotaku-ji is tucked away in a quiet corner of Matsumoto it takes a bit of effort to get there though it is certainly well within reach. Around 4 kilometers (2.5miles) from Matsumoto Station, it’s upwards of an hour walking at an easy pace. A better bet is to rent a bicycle from the city (for free!). There are (usually) bicycles available along Nakamachi-dori, at Matsumoto Castle, and in a few other spots around downtown. Check with the good folks at the visitor information center in the station or on Daimyo-cho-dori, just a block from the main castle entrance.

By the way, there’s one more detail to note. Kotaku-ji can be written two ways: 廣澤寺 and 広沢寺. Signs for either one will get you here.

Peace.

[googlemaps https://www.google.com/maps/embed?pb=!1m18!1m12!1m3!1d11173.764928362707!2d138.00242954666288!3d36.2213137436208!2m3!1f0!2f0!3f0!3m2!1i1024!2i768!4f13.1!3m3!1m2!1s0x601d0f2b6193ef23%3A0xdbcc3d2459cd396c!2sKotakuji!5e0!3m2!1sen!2sjp!4v1597299316972!5m2!1sen!2sjp&w=600&h=450]